The last conversation with my father

The chronicles of learning a language that was never my first. Oh, and that damn Duolingo owl.

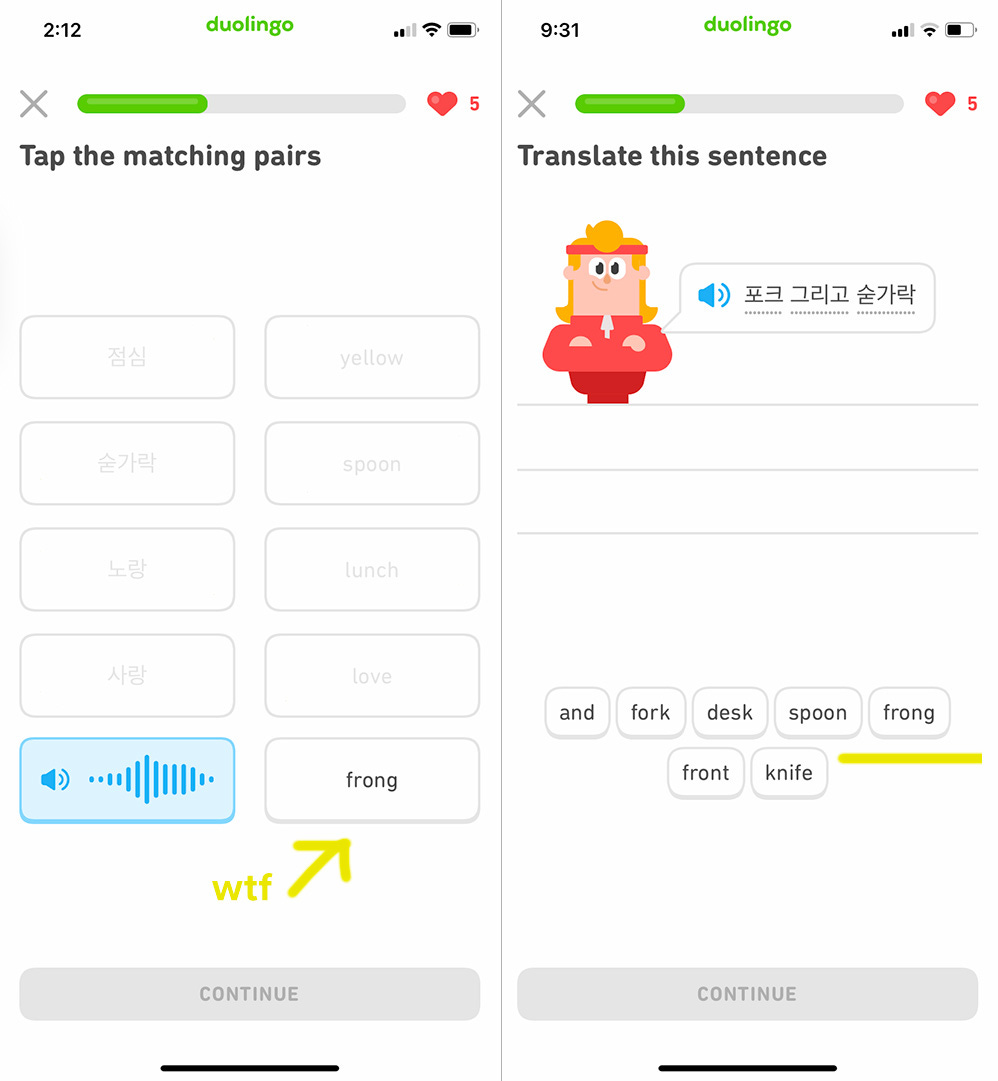

DuoLingo, I may have to break up with you

I’m sure there are many of you who have Duolingo on your phone and know what I mean when I say I have a love/hate relationship with that app. Well, love and hate are strong words so maybe it’s closer to “tolerate/dislike.” I’m currently on a 62 day streak. I’ve been on shorter streaks on and off since last year, but decided to see how long I can keep this one because, well…I hate to admit it, but I can’t deny my own competitiveness and now it’s just become a “thing” to spite that Duolingo mascot. Those push notifications manage to elicit both guilt and not-so-subtle pressure. I feel like I’m being passive aggressively bullied by that owl into opening the app if he senses that I might skip a day.

Would I recommend Duolingo to learn Korean? Probably not. I think it’s pretty bad for Korean and I actually said so once to a recruiter who was looking to fill a product design job at Duolingo many years ago when Korean just got rolled out (to be fair, I think it has improved some since then). The reason why I even have it on my phone in the first place is because I was doing research on gamification last year for a project designing a new app for a client and I thought I might as well use it to brush up on my Korean. I love multi-tasking! But Duolingo is actually terrible at teaching grammar—meaning it seems to skip over it entirely, and it’s wildly repetitive which I know is the point, but it gets tedious translating the same inane phrases over and over across multiple units in both Korean and English.

“The cucumber’s milk”

“I do not throw my friends”

That’s right Duolingo owl, I do NOT throw my friends!

Also, what is a frong. And a raccoon dog? Wait a minute, do I even know English??

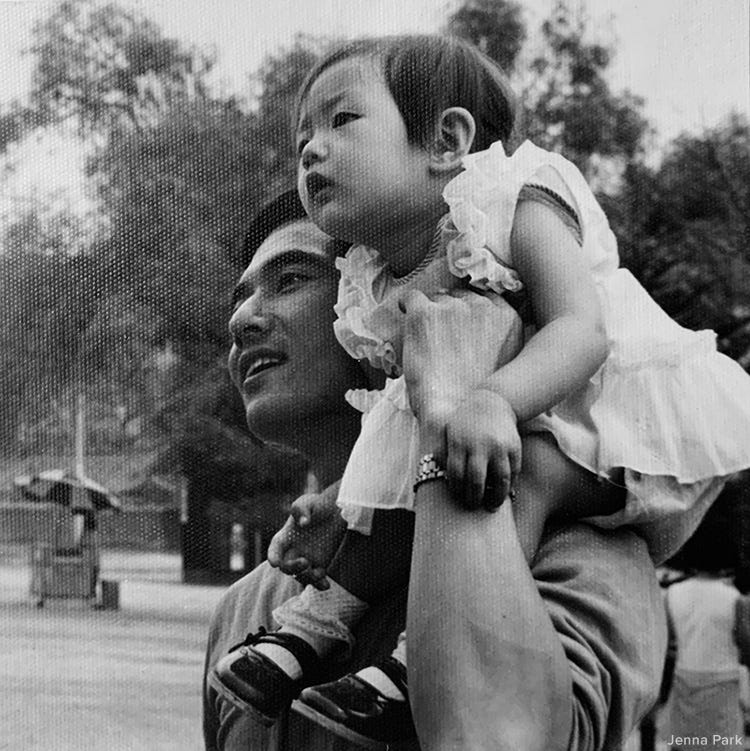

Whose fault is it that the children never learned Korean?

The recurrent issue in our household growing up was that neither my brother nor I knew how to speak Korean (you may know this from the newsletter about my mom’s book). We got by when we absolutely needed to by butchering the language badly and mumbling what probably sounded like incoherent pre-school level garble to a native speaker. When my dad had nothing else to complain about, he would complain that his children could not speak Korean. To him, this was bad reflection on his parenting to his peers (oh, how Asian is this?!). It wasn’t anyone’s fault really, but the subtext being raised in a patriarchal household like most Korean households back then, was that it was my mom’s responsibility to ensure that their offspring learn to speak the native language of their home country since it is the mother who takes care of all things related to child-rearing.

I’ve been connecting a lot of dots lately while I try to unravel a lot of childhood “stuff” and I do sometimes wonder if my disinterest in learning the language was some sort of subversive rebellion against my father. Whoa. This kind of blows my mind. But when I think about all the times the voice in my head would quietly scream in defiance every time he would get into one of his rants—“it’s not our fault that we don’t know the language! You’re the parent and that should have been your job!—maybe it’s not so far-fetched.

To his credit, my father would mostly talk to me in Korean. In return, I would always answer back in English. This never struck me as odd because we did this so seamlessly, but a friend who witnessed this back and forth banter between my dad and I pointed out that it was fascinating. It’s the auditory version of this:

“제니, 집에 언제 와?”

“I’m not sure, dad. Maybe we’ll come this weekend.”

“OK. 비오는 날씨에 운전하지마. 위험해”

“We won’t. See you soon.”

My dad and I conversed like this our entire lives. Once in a while I would throw in a Korean word or two and together, with my dad’s proficient but still broken English, we would communicate in a dialogue made up of the worst of each language. I suspect that this is fairly common within many immigrant families. Despite how it sounds, my dad and I didn’t really have a huge language barrier between us, but most of our conversations didn’t go far beyond the superficial.

I wasn’t Korean enough for some, and not American to others

I am what you call a 1.5 generation Korean American. The term was coined in the 70s and refers specifically to the generation of kids who came to the U.S at a young age. I came to New York City when I was three, so I barely had a grasp on my native language to begin with because I was just learning how to talk. This explains why my Korean was at a pre-school level, while some of my cousins who came when they were eight or older sound almost fluent to my ears. Those five or so additional years of full language immersion really make all the difference. The kids in my family, like my brother, who were born here in the US never really had a chance at any kind of fluency. When I came to America, I was rushed to assimilate right away, which is why Korean was not spoken as the first language in our house—at least when my dad was home.

When I was around eight years old, my mom enrolled me in Korean school every Saturday for eight months. This is where I learned the alphabet, how to read and write, and understand basic Korean conversation. But as with most language learners, the speaking part was the hardest. It still is, but those lessons set the foundation that enables me to pronounce the language sufficiently enough without sounding like a complete foreigner. It’s the difference between learning the language at an early age vs. later in life. I see my kid struggling to pronounce certain vowels and consonants correctly in their college Korean classes even though she has been around the language her entire life.

I think the worst impediment to learning Korean, however, was that any time I attempted to speak, I felt like I was being tested and mocked by the adults and native speakers in the room ready to pounce at the opportunity to correct me or laugh at my mangled attempts. The few times I went to Korean businesses in Flushing or K-Town without my parents were the times when I have felt the most judged and shamed for not being able to speak. This is the thing about being an immigrant kid—you aren’t enough of one culture or the other and you’re just stuck in this uncomfortable identity limbo of not belonging anywhere.

I remember a conversation that Mark had in the elevator with someone who picked up a TV from us off Craigslist:1

Korean man: “Oh, your wife is Asian? Korean, huh?”

Korean man: “Korean women cook good!”

Mark: “I do all the cooking.”

Korean man: “Wha?” (pause) But…Korean women cook good. Hmmm.”

Korean man: “Does she speak Korean?” (pause, then answers the question to himself quietly, shaking his head) “Probaby not…”

The last conversation with my father, through a window

My journey back to learning the language goes back to my dad. At around stage 5 of his Alzheimer’s, I noticed that he was speaking in English with less and less frequency. He would even speak to Mark in Korean which we all found pretty amusing. I was getting concerned that my relationship would end up like the one I had with my grandmother later in life, in that I wasn’t able to really communicate with her at all beyond the few basic phrases. Even though she was the person who raised me when I was a baby, it made my adult relationship with her feel complicated. I didn’t want that with my dad, and I vowed to finally learn the language once and for all.

My Korean learning didn’t really get too far though. Covid hit and most everything that did not include just trying to survive that year took a backseat. Then, in a span of that year, my dad’s Alzheimer’s progressed rapidly. My last interaction with my him before he died of Covid at the very end of 2020 was through a nursing home window.

I’m still processing that entire time period which is pretty clear given the wave of emotions that just hit as I type this, but we had a normal-ish conversation on Thanksgiving when he exhibited a miraculous flash of coherency. He told me that he was doing ok “at this place” and that he was looking forward to going home later. I asked him if he ate anything that day and he answered that he was going to eat soon, that they would wheel him to the other room. He let me know that the food was ok. He fidgeted with the ledge of the window with his fingers like he always did, but this time he looked straight at me when he spoke. He even seemed to remember who I was and had a glimmer of recognition of the kids who were standing behind me. When another family with a dog appeared for a visit with their mom at a nearby window, he pointed to the dog and expressed delight. He always loved dogs. This was a remarkable turnaround because for 3 months in the hospital and nursing home, he was incoherent and his mental capacity completely stripped, leaving him a hollowed out shell of the person he used to be. This is what Alzheimer’s does. It steals any shred of dignity and humanity from your loved ones in a slow burn progression toward life’s end.

I have read that dementia patients will often exhibit moments of clarity before the very end. It can sometimes give a false sense of hope—and in our case it did. He almost seemed like his old self that day. But it was short lived.

The last conversation that I had with my father was entirely in Korean. At the time I didn’t realize it would be our last, but I find it poetically fitting that this was the only conversation that we ever had between us that was spoken entirely in Korean. I don’t know what it saids about me that it took all of my adult life to come around to this, but I think about it all the time as I open that stupid app every day and listen to lessons on Youtube. All those years of harping on the fact that his children could not speak his native language. All those years of blame on his side and years of shame on mine.

I finally let my resistance to learning the language die alongside my father.

I’m learning a language that could have been my first had the winds shifted a different course in our family history. I’ve come to the acceptance that regardless of where I landed geographically, my culture is still inherently mine to claim.

I’ve printed this dialog before in a post about a different topic on my old blog. I realize that I might do this every so often—deconstruct old blog posts and pepper snippets here and there.

I just found your Substack and am so thrilled. So much of what you write resonates strongly for me. My mom is 92 and from Japan, and still in denial over being in the US. My Japanese is nowhere near fluent but I’ve worked so hard over the years to get better, and three out of my four kids even studied it in college. Language cuts to the core of who we are, and not being able to really and truly converse with our older family members hurts. Hugs to you and condolences. I’m so glad you had that conversation with your dad. I’m reading your entire archive, you have so much good stuff in there.

I felt this so much, especially the part about not being ___ enough and at the same time not being American enough. My parents speak Mandarin, Tagalog, and a dialect of Chinese that is only spoken in a small part of Asia. I grew up not speaking any of these languages fluently, yet languishing in disappointment when I tried to. Then being teased for pronouncing things incorrectly. My grandmother recently passed from a stroke + dementia and we were never able to communicate effectively, enough for me to learn about her and her past. Everything I know is through secondhand stories from my mom and her siblings. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and experience. With my own biracial kid, he is even further removed from my mother languages, and I can feel that part of me slipping away. This makes me want to try to do the learning together so we can have each other to practice with. Without the judgement or embarrassment.