The trauma of immigration, and the story behind a name

Names, luck, and destiny, and how I ended up being one of a million Jennifers.

In Korea, the practice of naming your baby was often determined by seeking the consultation of a fortune teller. By taking a thorough look at the baby’s birth date, the Chinese zodiac, and some mystical calculation of how well the elements of earth, metal, water, fire and wood combine in harmony with the birth date, the final name is selected. My mother once told me that I was born with a different name, but when visiting a fortune teller, was quickly advised that the name she had chosen was not auspicious and could lead to bad luck. I was given a new name for better luck and destiny. I don’t know if this practice is still common with newborns anymore, but Koreans believe that a good name can determine a baby’s fate.

My Korean name, my American name

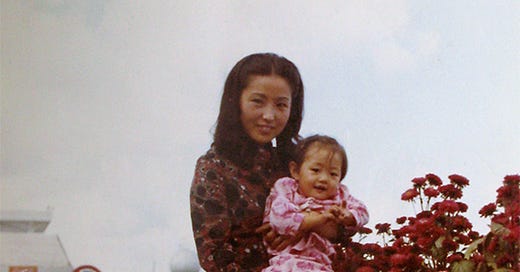

I came to America with the name, Hyun Jung. That’s the name written on my green card which I still have somewhere, laminated and tucked away with my other important documents. But it’s not a name that is easy to pronounce for American tongues and when that quickly became obvious, my mom changed my name to Jennifer before I was enrolled in nursery school.

As the story goes, my mother and I were walking down the street in our neighborhood in Queens when she overheard another mom call her daughter “Jennifer!!” She then turned to me and decided that I would be a Jennifer from then on.

It’s almost amusing how unceremonious and arbitrary my American name came to me, given how carefully my chosen Korean name was considered. What ever happened to names, luck, and destiny? But I imagine my mom was heavily weighing the convenience of having an American name when I was ready to start school. And like so many other factors having to do with immigrant assimilation, we change and compromise many things about ourselves—our identity, our appearance, our behavior—in order to conform. But this is also for the benefit of making interactions with others less challenging and awkward, even if it is at the expense of hiding who we truly are.

Millions of Jennifers

It should come as no surprise that as a child of the 70s, my mom gave me the most common name from that decade. The story of how she named me Jennifer right there on that sidewalk might be partially fabricated (who really remembers), but she undoubtedly heard and saw the name everywhere. I’ve read that Jennifer became wildly popular because of Ali MacGraw’s character in Love Story. It’s curious that a film about a heroine’s tragic demise launched a million Jennifers for the next dozen years (talk about names and fate!).

In my mother’s attempt to assimilate me as quickly into American culture as possible, it’s wildly fitting that I was given a name that would personify an entire generation. I personally know about a dozen Jennifers, all 70s babies. If her intention was to have her Korean child blend right into American schools, at least on paper, then mission accomplished, but my American name didn’t always make it to the classroom roster list on teachers’ desks because my name was not official and wasn’t printed on any government documents.

Because of this, I always dreaded the first day of school. My body would brace itself for the inevitable butchering of my name. I always knew I was next when there was hesitation after a string of Lisas, Johns, and Michelles rolled fluidly off my teachers’ tongues during attendance. My shoulders would tense as I heard them struggle to pronounce the first few letters, my face growing hot with embarrassment every time I raised my hand to claim the foreign name. I waited for the snickers and taunting echoes of my mispronounced name that I knew would always come.

“Your name is Ching Chong!”

Sometimes you can never unhear things.