The end of the multi-hyphenate

In art, context often matters. How revisiting an old project gave me an understanding of my artistic paralysis.

Twenty years ago while on a project for the Smithsonian, I had the special opportunity to visit the photographic archives spread across its many museums and research centers in D.C. It was an archivist and historian’s dream: aisles and aisles of vertical files, endless drawers of ephemera, the scent of aged books.

The Smithsonian owns a staggering 13 million+ photographs. It had never before been accessible to the public. Not surprisingly, the challenge of designing the institution’s first photographic online museum was a huge undertaking. How do you aggregate such a massive collection of images and make it searchable and accessible to the general public? How do you democratize the meaning of imagery?

To my amusement, I was reminded that to illustrate the sheer volume of what 13 million photographs even looks like, I created three separate minute-long videos of images choreographed to music. This was 2006. I laugh because they were essentially…reels.

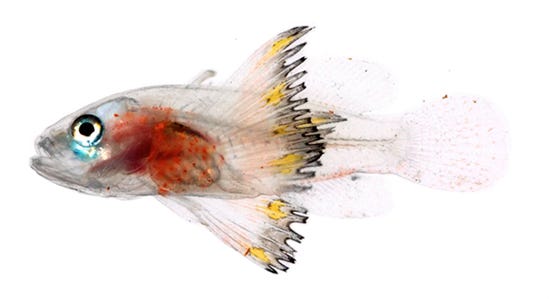

My team and I spent months of research to get our heads around the thesis of classification and taxonomy. But it was this specific, illuminating moment listening to the curators at some of the museums that blew our minds: they didn’t view the images as art or even as photography. In their minds, they were documentations of specimens and historical artifacts.

“These are not photographs. They are photomicrographic studies of snow forms,” the curators would insist as we sifted through a small sample of the hundreds of individual closeup snowflake photos taken by Wilson A. Bentley in the late 1880s.

Likewise for the tens of thousands of images of Native Americans and the thousands of specimens of fish in the museum’s collections.

But to us designers, the images were undeniably art.

The language of imagining and how it’s constructed matters. Context matters—and in the case of the Smithsonian, the particular museum a photograph was housed in mattered a ton. For example, I was struck by the boxes of family albums in the storage room of one museum, the kind of boxes of old photographs that you and I might have in our homes. The photos were catalogued as anthropologic artifacts of collective American history, but some of the images could have been considered fine art photographs if housed at a different museum.

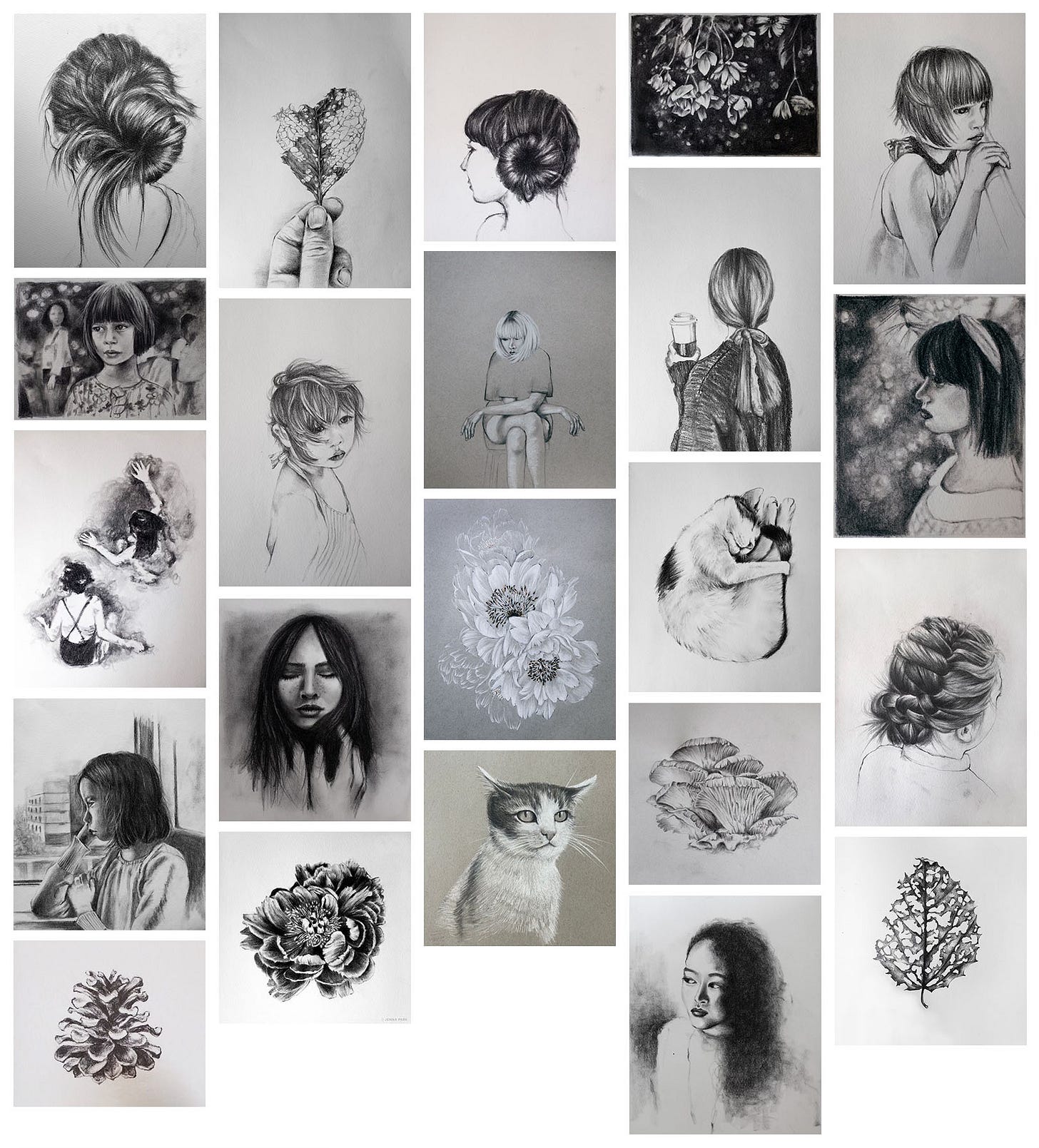

I was thinking about this project recently because I’ve been trying to dig into why I’ve been so artistically paralyzed for years. Drawings made this year have marked progress in output, but when I look at them I’m unsatisfied.

This is where context comes in. To others they may be art, but to me they are observations transcribed in visual form; I am like the archivists who sees the photographs as documents. I can translate an object into a drawing, but what do these drawings say? Interestingly, together in a grid, they might start to tell a story.

I’ve written about my struggles with art for as long as I’ve been writing here. It was nearly a year ago that I announced that I was saying goodbye to my career. I had hoped that by stepping back, I wouldn’t have to divide my creative and mental energy between client work and art.

As it turns out, life always has other plans. Household job fluctuations means picking up the financial slack. Once a breadwinner, always a breadwinner. But what gnaws at me is my seeming inability to work and do art on my own at the same time. Lots of artists make this work, so why couldn’t I?

I gained some clarity a few weeks ago when I posed the question, are we writers or are we content creators? Through writing and exchanged dialogue, I was able to start deconstructing what was blocking me for so long. After more than 25 years of being a multi-hyphenate human being in my career and in life, I was just feeling done.

Many of us are multi-hyphenates at our jobs, particularly if you’re entrepreneurial or work in a creative industry, so it’s nothing unusual. One could even argue that modern work life requires it to some degree. My career certainly didn’t follow a linear path. I thrived at being a multi-hyphenated designer. I could never stay in one lane and it served me well as a business owner too because we didn’t need to outsource the creative part of running a brand that sold physical products. I wanted to do it all—work with sound, video, animation, data, and nerd out as much as I needed to as a UX designer.

But as I continue to wrestle with this long-tail transition into semi-retirement, the less multi-hyphenated I want to be. I even have a strong resistance to it. Blame it on age and menopause brain fog—I don’t know and I don’t really care, but I no longer have the desire or the stamina to do everything. I just want to channel my energy on one or two things.

I’m learning that my gut was right when I long ago shelved art making as something that I’d probably get to in retirement. I was cognizant enough to know that to be the artist that I wanted to be, I needed time. But not just any time—undivided and unfettered time, free of creative diversions from clients or even the mental weight and responsibilities of being sandwiched in between two generations. Art represented freedom. Maybe my younger self knew myself better than I thought.

Art is deeply personal. For most of my adult life, anything creative that I’ve outputted as a designer or a business owner has been transactional. Even this Substack has a transactional element. But at some point, I decided that art to me was too personal to be transactional.

Words, at the moment, is how I coalesce the chaos and beauty of life into something tangible. It’s my wish to be able to do that visually too. I once made a classmate cry when I played a piece for the piano that I had written for a music composition class, but I don’t know if I’ve ever moved anyone like that with my art. That level of soul bearing requires plunging deep to unbury the things I can’t even see. It requires sitting in discomfort. To live with despair and pain for a time. It’s a deeply vulnerable place. These are not easy issues to tear apart and examine. Cultural identity. Childhood trauma. A brother’s suicide. Abandonment and loneliness.

Are these excuses or an intentional act of procrastination? Perhaps. But it’s not something I can rush.

And so, I draw the things around me. A practice benign enough to feel that I’m creating and making, joyful enough to be calming, but infinitely easier than delving into the dark corners of my soul.

Related Reading

What I enjoyed this week

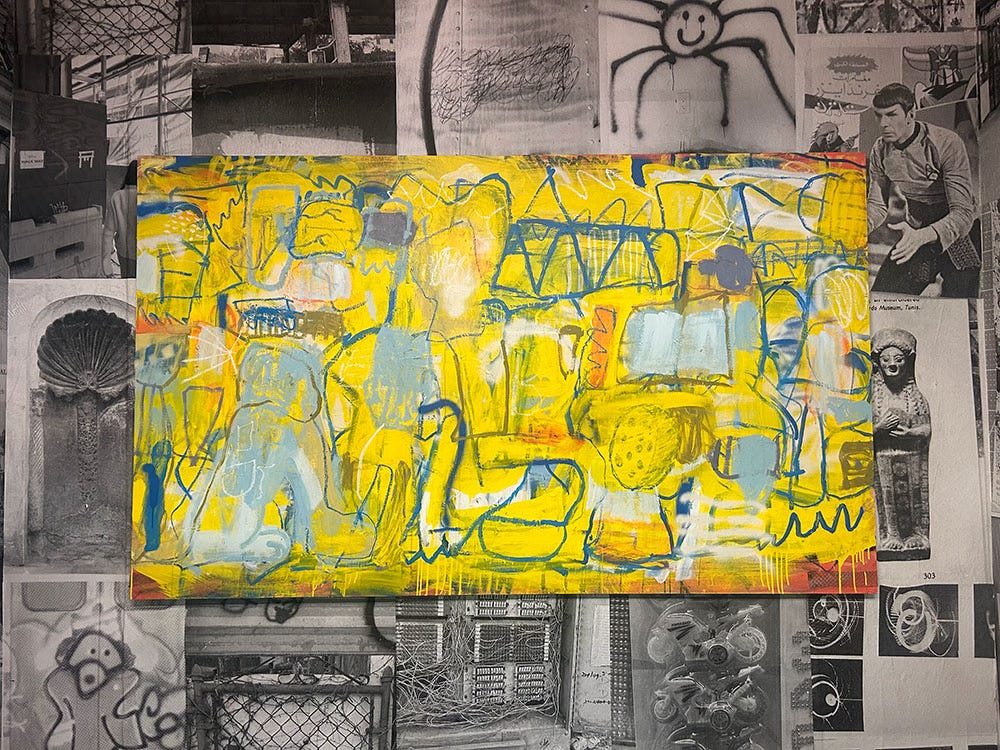

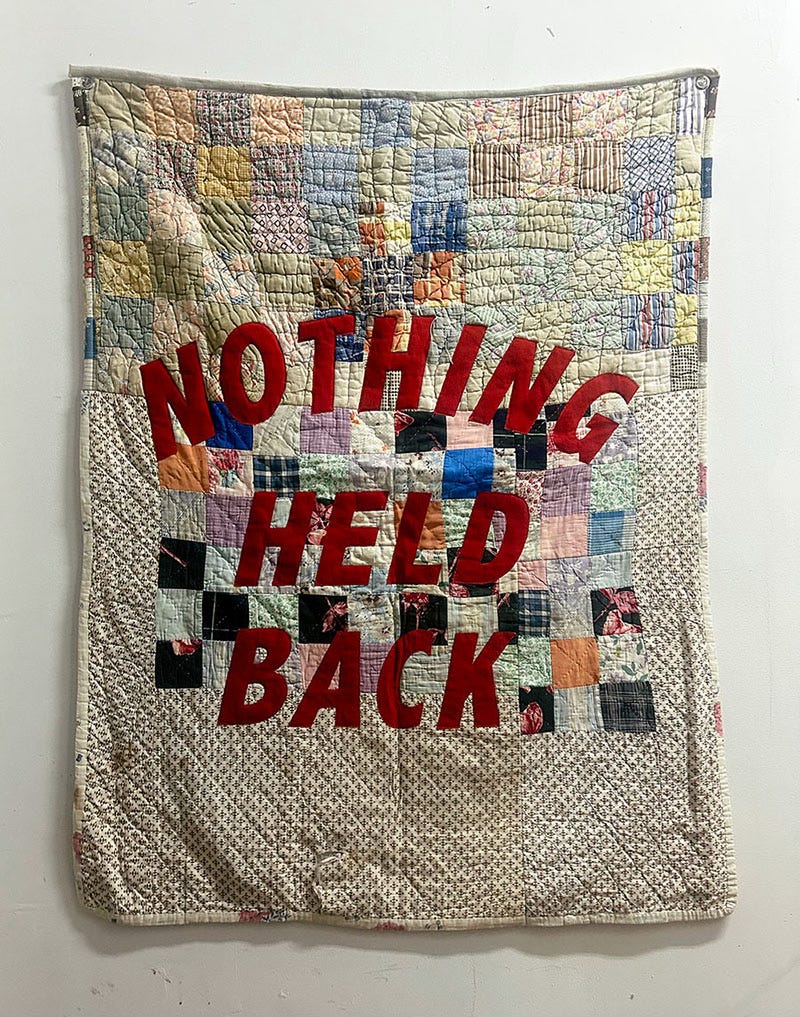

Every year, hundreds of artists in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn open their studios in October for a weekend celebration of local art. I’ve missed it the past few years, so it was a pleasure to walk around last weekend and step inside some of the old warehouses and factories that have been housing artist studios for decades.

Like many artist enclaves in NYC’s past, gentrification poses a threat to affordable spaces for artists. Gowanus is no exception and it’s changing faster than I’ve seen any neighborhood transform in recent years. I’ve lived adjacent to this neighborhood for nearly 25 years now and still discover new spaces that surprise me. It gives me hope that vibrant artistic communities like this one can coexist alongside gentrification and not only survive, but thrive.

Kafka’s Creative Block and the Four Psychological Hindrances That Keep the Talented from Manifesting Their Talent (The Marginalian)

“The most paradoxical thing about creative work is that it is both a way in and a way out, that it plunges you into the depths of your being and at the same time takes you out of yourself.”

This essay from Maria Popova is so very relevant to this week’s newsletter.What Can You Learn from Photographing Your Life? (New Yorker)

“Photographs, even mundane ones, pause and magnify. They let us look, and look, and look at what our roving eyes pass over.”

Also very relevant to recent newsletter writings. Still haven’t managed to clean up my camera roll. I give up.A Love Letter to Public Libraries (34th street)

I was really very happy when my kid started to go to our public library her senior year to study and work on her personal college essays. Public libraries are invaluable community hubs and resources that should be protected, not subjected to budget cuts like the ones faced by NYC libraries (it was reversed).On Walking Alone at Night (Image)

Mindy Misener takes us on an evening walk with her in her Midwestern town and narrates her observations along the way.

I feel this on a soul level. Years and years ago, I was eavesdropping on a conversation in my local coffee shop. The woman, a yoga teacher, was mentoring another woman, who I guess, was starting to teach yoga herself? Anyway, here's what she said:

"I found that for many of my students, you have to exhaust them before they can relax into the deeper poses."

And at the time I'm sure I rolled my eyes, at least slightly. The whole scene was all a little too cliché. But I've thought about that little snippet for, like, a full decade now. And I know why it's been so sticky: I am that type of student. Gah!

So, I'm here for the era of the multi-hyphenate coming to a close. And, in this time of fast-chain-franchise-media consumption, art is essential. At least for many of us. Thank you for making it and sharing it with us. xo

If the election goes smoothly and the way the sane people want it to, I feel like a great weight will be lifted and by Spring, we might collectively all have some energy again. 🤞🏼