Saying goodbye through a pandemic window

Recounting the last days with my father. How do you reconcile the holidays when it's also the anniversary of a passing?

My dad once gave me a fruitcake when I was 15. He came home with it one Christmas Eve, all smiles as he handed it to me as if it was the most precious gift in the world. I know this may sound odd, but when I think of my dad, I often think about that fruitcake and my 15 year old self, sitting alone in my room eating my way through that cake. I devoured the whole thing and not because I enjoyed it, but because at the time it was the only gift that I could recall my Dad ever giving me.

For an entire week, I shoved forkfuls of dense fruitcake into my mouth, chewing on chunks of candied fruit until it was all gone, as if I was somehow trying to consume and internalize all of my conflicted teenage feelings about my relationship with him.

There’s an unsettledness to death when you’re robbed of a chance to say a final good bye. There’s an unsettledness to death when it comes to someone you had a complicated relationship with.

This is probably why my mind wanders towards innocuous memories like that fruitcake because these memories feel like a safer space to stay in.

Death can be violent, but also a release

I know, collectively, we’re so done with the pandemic, but I need to tell you how unnatural it is to watch someone die from behind a pane of glass through a window or a phone screen. I need to tell you that death isn’t always peaceful in the way that it plays out in movies where the dying is surrounded by loved ones and slips peacefully into the light. The active state of dying, as I learned from watching my own father, can sometimes be violent and in that first Covid year, also very solitary.

In 2020, nobody in their right mind would have willingly admitted their loved ones to a nursing home when such institutions felt like death sentences, but this is how desperate you are when you fight Alzheimers. This isn’t a disease that only strikes the afflicted, this is a disease that takes an entire family down with it.

At one point, I was worried about losing my mom to a heart attack from all the stress of caregiving or that she would be a victim of his sometimes violent Alzheimers outbursts. If you don’t believe that stress could manifest itself in physically detrimental ways, I now have minor, but permanent nerve damage from an illness diagnosed during this time, like a scar that proves otherwise.

The last time I was in the same room with my father was in the hospital where he was taken after he took a fall just hours after we moved him into a memory care facility. He was unrecognizeable. With an IV line of antipsychotics pumped continuously into his veins, his glassy eyes darted wildly as he babbled incoherently. I have never seen anyone talk non-stop for so long without even taking as much as a pause, but apparently this is not unusual when a patient is in a drug-induced psychosis. I later learned from nurses that he was talking in this manner for days.

When I first approached him in his hospital room and heard him mumbling in a soft, barely inaudible whisper, I thought he was speaking to me. But I quickly realized that he was completely gone in his own world and he was having conversations with everyone but me, his eyes darting around the room because he was likely hallucinating. In his mind, we were not alone in that room.

There were moments, however, when his eyes would briefly meet mine. These were the rare pauses that I saw him take. They only lasted a few seconds, but in that fleeting moment, standing there holding his hand, I forgave him for all the wrongdoings that he did not deserve to be forgiven for. Despite the life that he lived, nobody deserves the indignities of this illness. Not even karma should be this cruel.

You might think that this visit was hard—and it was, but it was also peaceful in a strange, surreal way. In his conversations with the imaginary, he would smile and even laugh. This kind of blissed out dementia is the best state that one could hope for, not the violent agitated outbursts that he exhibited for so many months that made him impossible to care for at home.

The agitation was the reason for the antipsychotics, the reason why my days and nights were consumed with anxiety because my greatest fear was not finding a nursing home that would take him after his hospital release. In my desperation, I researched the last resort option, if it came to that: to give my dad up as a ward of the state in a geriatric psych facility. The only thing I knew for certain was that I couldn’t allow him to come back home. Luckily, to our relief, it did not come to this.

I crossed paths at the hospital entrance with my mom, who came to see him after my visit. I let her know that he seemed “ok,” only to get a text from her an hour later with a photo of him thrashing in his hospital bed, sheet uncovered, with his head at the foot of the bed and legs draped over the sides in an episode of agitation. Even in that state of psychosis, he saved his worst behavior for my mom and spared me the ugly, just as he always had.

Earlier this year, I wrote about the last conversation I had with my father on Thanksgiving. I never thought that he would come out of his psychosis, but he did, though he was never the same after his two week stay in the hospital. It was a miraculous turnaround standing in front of that nursing home window, him on the other side in a wheelchair peering at me from between an open crack. We had the most mundane conversation about food and the weather, just like all the other superficial conversations we had with each other our entire lives.

That holiday season, right before Christmas, was when the second deadly wave of Covid hit New York. You may remember this from the news. My dad was among the dozens who tested positive in his nursing home on Christmas Eve. I went to see him on Christmas day, standing outside the window, but this time he wasn’t in his wheelchair on the other side of the glass fidgeting with the window sill like he did during other visits. He was laying in his bed, sleeping with his mouth slightly agape as he was gasping for air, hooked on oxygen. He looked noticeably parched and so, so small. He did not look like the living.

I was told by the nurse that he fought the IV that they attempted to put in him multiple times that would have pumped critical fluids and meds. I imagine he was in great pain, but it wasn’t possible to give him a morphine drip and the doctor gave him two weeks to live.

But my mom knew better. She watched him from the window for the next few days, where he was left alone for much of the time due to a severe staff shortage because nurses and CNAs were terrified to come in when Covid spread again. She would call me on the phone in anguish.

“They’re killing him in there!”

“I want to bring him home!”

In a panic I begged her not to bring him home. I told her that she would catch Covid too and I didn’t want to lose both my parents at the same time.

A few days after Christmas, the phone rings again. My mom is outside his window and she tells me that it’s time.

“But the doctor said it could be weeks!” I protest.

She was timing his breaths for an hour through the window, something she had done with other patients for 20 years as a nurse in her former life. She knew what death looked like even through a pane of glass.

Later that night, my father passed away, alone in his nursing home room.

—

I often think about how the two men in our family both died alone—my brother by his own hand in a hotel room extinguishing his own pain while my father in his nursing home could do nothing but lie in that bed and wait till his physical body gave up. I think about the parallels and the weight of that symbolism, though I’m yet to figure out what that means to me and if that has influenced how I think about death.

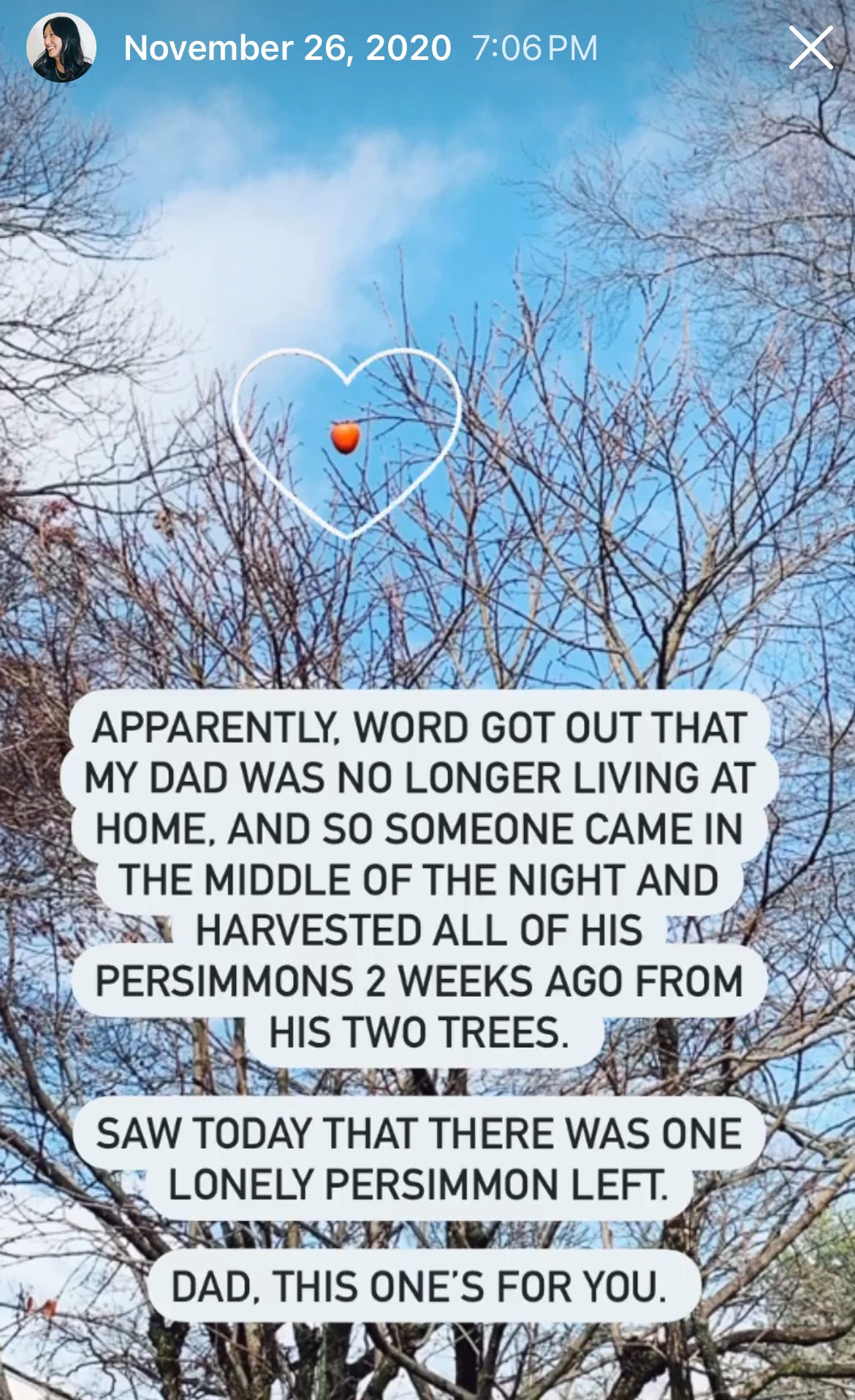

I also think about the persimmons that were stolen from his prized persimmon tree in the front yard of his house that Fall. Again, maybe this is the safer memory that I choose to stay in, much like the fruitcake. I was so angry to see the tree all bare when we drove up to the house right after a window visit. The ripe persimmons were all plucked in the middle of the night when word got out that my dad was sent to a nursing home. There was only a single, plump, orange fruit perched at the top of the tree that was too high to be reached. At least the thieves left one for him.

Despite how horrible all of this was, I am grateful that Covid took away my dad’s suffering so swiftly from an illness that was slowly killing him. It gave my mom her life back. I’ve learned that it’s ok to feel gratitude for both of those things.

And in a blink, we’ve entered the holiday season again.

I don’t how many years it will take for a holiday to go by without the inevitable malaise and melancholy that creeps in once November sets in. Maybe it won’t ever. The expectations to be merry during the holidays is a joy for others and a burden for some. But it can also be both, and that is the space I sit in.

If you are in this space with me, I see you, and it’s ok that the holidays are hard. But you are not alone.

-Jenna

Related reading:

The last conversation with my father

On this father's day, a story about wigs, a story about New York

Thank you for sharing this very vulnerable side of you and allowing us to sit with you in this space. What a gift to everyone ❤️ these are the kind of conversations that heal us.

Beautiful. I feel more grounded, more human, after reading this. Sending love